Dieser Beitrag ist auch verfügbar auf:

Deutsch

An old man wanders through the house at night. He’s wearing five shirts on top of each other, and his pockets are stuffed with silverware, towels, and a toothbrush. He says he wants to go to school. A woman suddenly yells at her grown daughter, asking who she is and claiming that she is stealing her things – only to cry like a little child seconds later. The diagnosis in both cases: Alzheimer’s disease. About 7 million people in the United States alone suffer from dementia.

What happens in the brain when we have Alzheimer’s?

The generic term dementia refers to any condition in which a person loses almost all mental functions, such as thinking, remembering, orientation, and connecting thoughts. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease. It affects two-thirds of people. Nerve cells in the brain slowly die, one by one, years before the first symptoms appear.

The cause of nerve cell death is a faulty metabolic process in the body involving a type of protein. Either too much of it is produced, or the body does not break down the protein deposits properly. Like a poison, the protein then attacks the nerve cells, synapses, and energy-producing mitochondria, causing them to die.

What triggers the faulty metabolic process?

Some doctors are still struggling to find the answer to this question. The causes of the very difficult to find early cases of Alzheimer’s, which often occur within a family, are best known. Here, errors in the genetic material, so-called mutations, trigger an excessive production of proteins. The symptoms of hereditary Alzheimer’s disease usually appear before the age of 60.

Several factors play a role in non-hereditary Alzheimer’s dementia. The most important is age. While Alzheimer’s affects only about one in a hundred 60-year-olds, it affects one in ten 80-year-olds and one in three 90-year-olds. Genetic factors also play a role. However, they do not cause the disease, but only exacerbate it. According to the German Alzheimer Society, people who have had little mental, social or physical activity in their lives are also more likely to develop dementia.

The psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer first discovered these changes in the brain in his patient with dementia, Auguste Deter, over 100 years ago. At the time, he still thought he was dealing with a very rare disease. In 1996, doctors Volk, Gerbaldo and Maurer discovered Auguste D.’s medical records in the archives of the psychiatric clinic in Frankfurt.

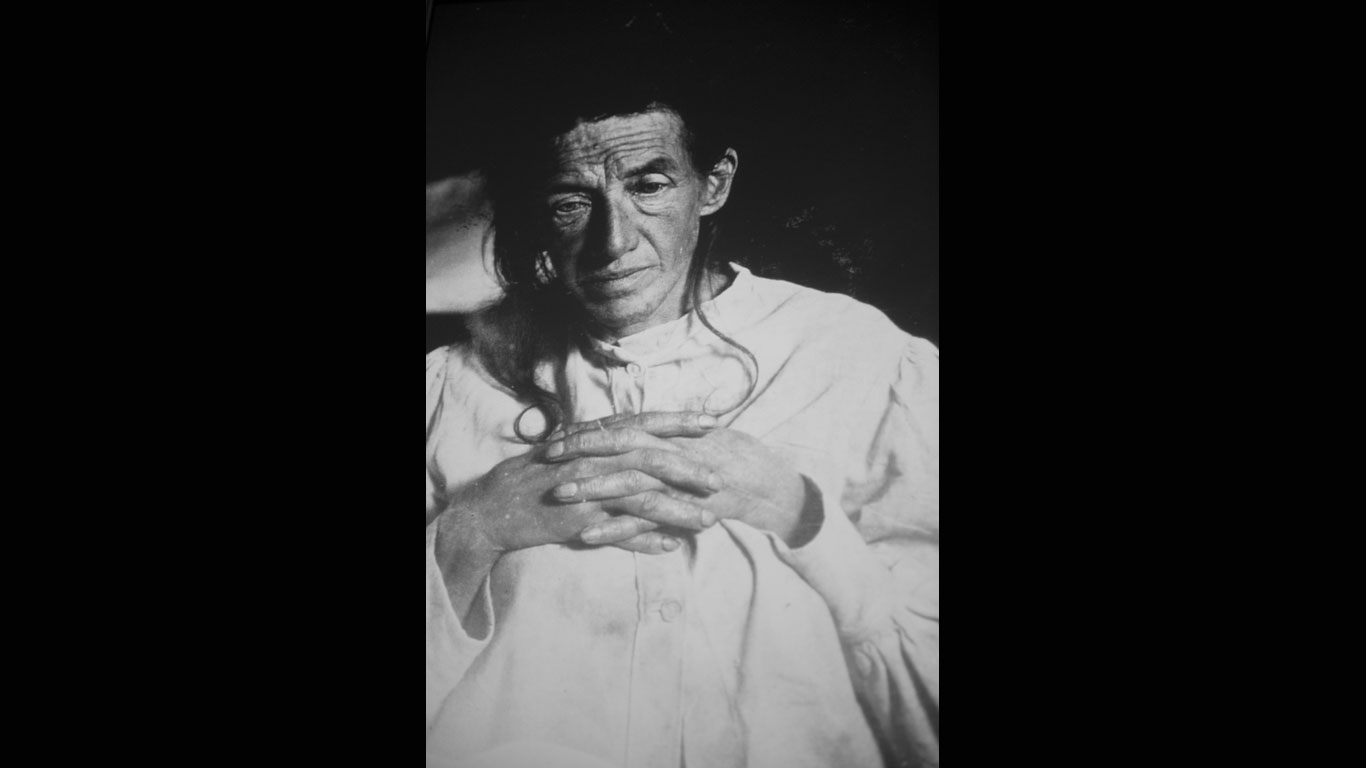

Auguste Deter

The case of Auguste Deter captivates Alois Alzheimer. Auguste is brought to the asylum in 1901 by her husband, confused and disoriented. She is only 51 years old and seems otherwise healthy. After her death five years later, Alzheimer examines her brain and discovers massive cell atrophy and unusual deposits in its tissue.

Symptoms - mild dementia

In the early stages of the disease, short-term memory in particular no longer functions properly. Those affected forget what they talked about with their neighbor recently, or where they put their reading glasses. They are often confused when family members or friends mention things that they cannot remember. They increasingly find themselves in unpleasant situations due to their condition. However, they are still largely independent in their everyday lives.

Symptoms - Moderate dementia

People with moderate dementia find it increasingly difficult to cope with everyday life on their own. As their ability to think, remember and navigate deteriorates, they need help with the simplest things - such as shopping or personal hygiene. Gradually, memories of events from the distant past are also lost, which often manifests itself in the fact that those affected can no longer remember the names of their own children.

Symptoms - Severe dementia

People suffering from advanced dementia often completely forget how to speak. The entire body rapidly deteriorates. As a result, those affected can no longer control some bodily functions independently, such as going to the toilet, are more susceptible to infections and can no longer walk without help. Without 24-hour care and support from family members or in a nursing home, those affected would be completely helpless.

Rudi Assauer

In 2006, former professional soccer player and manager Rudi Assauer was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. The avid cigar smoker fought a long battle against the gradual progression of memory loss. Assauer died at the beginning of 2019.

Peter Falk

Many of us will always remember Peter Falk in his role as Columbo. He himself forgot about his legendary persona just two years after his Alzheimer's disease became known in 2007. He died in mid-2011.

The “Auguste” case

Frankfurt in 1901: Alois Alzheimer works as an assistant doctor at the municipal sanatorium for the insane and epileptic. On November 25, a man brings his confused and disoriented wife to the asylum. Her name is Auguste Deter and she is 51 years old. The following conversation that Alzheimer had with his patient Auguste made medical history: “What is your name?” – “Auguste.” – “Your family name?” – “Auguste.” – “What is your husband’s name?” – “I think … Auguste.” Physically, the woman appears to be in perfect health, and the doctors can also rule out psychological trauma. Alzheimer and the woman’s husband are mystified. Alzheimer recorded his observations on 31 pages.

In the early 20th century, brain research was just beginning to become widely recognized

In 1904, Alois Alzheimer leaves Frankfurt to head the Brain Anatomy Laboratory at the Psychiatric Clinic in Munich. He regularly inquires about Auguste Deter’s state of health. When she dies two years later on April 8, 1906, he has his former patient’s medical records and brain sent to him. Under the microscope, he discovers massive cell atrophy and unusual protein deposits in its tissue.

Six months later, at the 37th Assembly of Southwest German Psychatrists, he reports on the peculiar clinical picture and a “peculiar severe disease process of the cerebral cortex”.

As brain research had not quite become mainstream, Alzheimer’s contemporaries did not really take his discovery seriously, treating it as a mere curiosity. By the turn of the century, however, many doctors were examining brains under the microscope, using dyes to visualize structures and describing changes in the brain. But Alzheimer was the first to link protein deposits to memory loss in a younger patient.

It is never too early to diagnose Alzheimer’s and take action

Our society’s responsibility toward Alzheimer’s patients does not extend only to their families and physicians. Society must be made more aware of the disease and how to recognize it. Whether it’s the elderly woman who walks through the city center in winter without a coat, or the elderly citizen who withdraws unusually large sums of money from their bank account or buys bread from the bakery three times a day.

It is important not to look the other way. People with Alzheimer’s usually do this themselves because they are ashamed and frightened by their forgetfulness. Alzheimer also recognized fear, mistrust, rejection, and despair in his patient Auguste. In her conversations with him, she admitted that she had “somehow lost herself. Alzheimer spoke of the “disease of forgetfulness” – it was only after his death that it was named after him. He died in 1915 at the age of 51, even younger than his patient.